Why did we miss the bus?

An exploration into why India did not have its own Industrial Revolution despite its rich scientific history.

A frequently asked question

Nobel Laureate Abdus Salam had asked a question that historians of science have discussed from time to time. The background to the question is outlined first.

The scientific history of the Indian subcontinent, by no means complete, suggests that from the Vedic times about two millennia ago, India was perceived as a storehouse of knowledge. Scholars from neighbouring countries visited the subcontinent for consultation, translation of manuscripts, etc. What may be called the golden age of Indian science is sandwiched between the works of Aryabhata (5th Century A.D.) and Bhaskara ( 12th Century A.D.).

However, afterwards, the scientific momentum fizzled out. There were no major developments in this field, while the growth picked up on the European front. Copernicus and Galileo, followed by Newton, Kelvin, Faraday, and Maxwell, are some of the leaders whose discoveries led to the Industrial Revolution in Europe.

The question we wish to raise is: Why was there no industrial revolution on the Indian subcontinent?

Salam’s comment

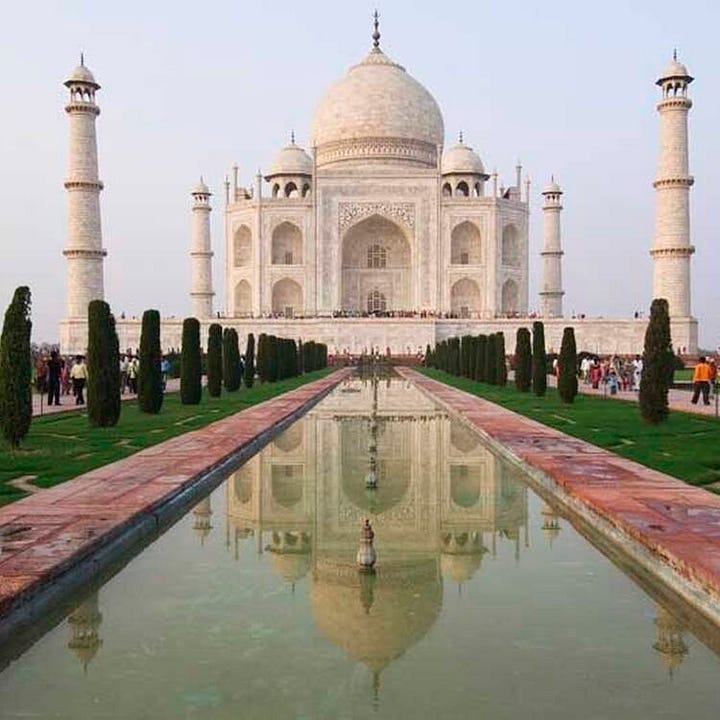

Nobel Laureate Abdus Salam expressed the above question by drawing attention to the following history. He mentioned that the Taj Mahal in Agra and St Paul’s Cathedral in London represented epitomes of architecture in India and Europe, built around the same time. Taking this as standard, one could see that shortly afterwards Europe witnessed the onset of mathematics and science through the works of Fermat, Newton, Leibnitz, Bernoulli, and many others. In India, however, there was not a single person to carry the mandate of Bhaskara.

Royal patronage for work in science and mathematics, which was available in Europe, was lacking in India. The Sultans and Maharajas did encourage and support culture in various forms, such as music, art, architecture, etc., but there was no example of royal support for a mathematician.

In addition to the royal families in European countries, highly placed barons and wealthy patrons of the arts also provided financial support for scientific research. We do not have a single example of such support in India.

An important consequence of this lack of native support was that it led to rulers in India ordering and buying guns, strategic instruments etc., from European rulers. Why did they not set up their own manufacturing and R&D units?

Incidentally, it is said that the British took control of the Indian subcontinent by employing a ‘divide and rule’ policy. While politically, this may be pertinent, it ignores the important role of advanced weapons and the communication facilities like railways.

Science vs. superstitions

The episode of Karmanasha Bridge illustrates the difference in attitudes. In the eighteenth century, it was felt that building a bridge on the Karmanasha river near Kashi (Banaras) would be highly desirable from commercial, social and infrastructural perspectives. However, the local talent could not erect the bridge: it would collapse while under construction. After this happened 3-4 times, the Local Administration sought advice from “expert astrologers” who diagnosed the cause as arising from the ill effect of the local deity. It recommended conducting a religious ceremony accompanied by a generous distribution of alms at the site. The demand for funds for this purpose reached the headquarters in Pune and the desk of Nana Phadnis. Nana was a practical man and had no sympathy for superstitions. What did he do?

He approached Baker, a trained English engineer in Calcutta, for advice and action. Baker visited the site with his instruments. He diagnosed that the bridge kept collapsing because no attention had been paid to its foundations. He got the water pumped out and created a firm base for the bridge. He left it standing–in fact, many bridges built by the British two centuries ago are still standing!

Indeed, science made progress on two fronts. On the ‘pure’ front, it concentrated its efforts on the ‘what’, ’when’ and ‘why’ questions posed to Nature. The answers gained often led to the creation of new devices that made life more comfortable. This ‘applied’ side prompted the Industrial Revolution.

Why did we miss the bus?

In the West, except for the well-to-do, living conditions were hard. Bitter winters, severe epidemics, and internecine wars took their toll. So, there was an incentive for the citizens to look for better locations. This was the incentive for colonization. When science and technology provided means for travel and better living conditions for those who took the risk, colonization, in turn, encouraged the Industrial Revolution.

In the East, by contrast, relatively mild weather and fewer problems for survival made travel less attractive. Also, religious sanctions forbade leaving one’s country. Thus, scholars from China, Persia, Greece and Arabia visited India… but there was hardly any reverse traffic. These social reasons also contributed to stagnating the growth of science in India.

It has also been pointed out that religions followed in India were generally tolerant. They emphasized the importance of simplicity and the need to live on very simple needs. An attitude of this kind is socially admired, no doubt. However, it does not provide any incentive for material progress. So when the bus for the Industrial Revolution passed by the Indian subcontinent, there were no takers for a ride.

sir, what are your views on roddam narasimha's answer to needham's question "why did scientific revolution not take in china and India despite being them leading 14 previous centuries?"

Very insightful. Do you think the same logic applies to other non-europe regions mainly China, Southeast asia and middle-east that missed the IR bus as well.