The IUCAA Story: Part 2

Inter-University Centres

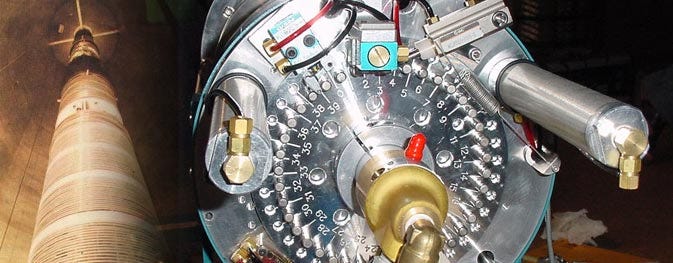

As mentioned earlier, the growth of science in India was such that the universities felt ‘left out’ in the usage of advanced facilities. To deal with the problem, the UGC decided to create centres of excellence in various fields, with the users being faculty and advanced students from universities. Through an act of Parliament, the UGC was empowered to create such centres. The Nuclear Science Centre, now renamed the ‘Inter-University Centre for Accelerator Sciences,’ was the first such centre, created on the campus of Jawaharlal Nehru University. It was centred around the nuclear accelerator pelletron with state-of-the-art technology for studies of nuclear structures.

A second centre was on the cards, related to astronomy and astrophysics. I was destined to be involved with it!

To briefly describe my background, after a fruitful career as a founder member of the Institute of Astronomy (IOA) in Cambridge, I returned to India in 1972 to join the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR). I had joined the institute with a mandate to grow its activities in theoretical astrophysics, and over the sixteen or so years there, I had the satisfaction of seeing that objective accomplished. Although I was happy with my work, other issues were beginning to weigh on my mind, issues that were to take me on an adventurous journey away from TIFR.

TIFR had been set up by Homi Bhabha to help create and strengthen the base for fundamental research in the country. The expectation was that scientists trained here would contribute to applied research in related fields and to universities by enriching their faculties. The first happened to some extent, e.g., through the setting up of major scientific establishments like the BARC, SAMIR, NCST, etc., by the talent drawn from TIFR. The benefits expected by the university system, however, did not materialize. Although in 1946, when the TIFR was set up, the conditions in a typical university were academically reasonable, these declined sharply in the 1960s. For various reasons, including this circumstance, there was no significant transfer of faculty from TIFR to Universities. Except for the School of Mathematics, there was no significant collaborative venture between the TIFR and Bombay University.

Indeed, in the 1980s, there was a growing realization in my mind that there was a need for centres of excellence exclusively within the university sector. Indeed, the parent body of universities in India, the University Grants Commission (UGC), had appreciated the need and, to address this issue had decided to create its own centres of excellence, the ‘Inter-University Centres’ (IUCs).

I saw here a fresh opportunity to revive astronomy and astrophysics within the university sector. Could we create a centre that acts as a resource not only for material facilities but also for intellectual stimulation for the faculty and students of universities? Although the projected setting up of the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope near Pune was one reason for bringing IUCAA into existence, even without it, enough exciting challenges existed. Challenges that I was missing at the TIFR.

My brainstorming discussions with scientific colleagues, starting with Naresh Dadhich, a general relativist at Pune University, were productive enough to interest the UGC in the possibility of creating an IUC in the field of astronomy and astrophysics. As a result, the UGC asked me to submit a proposal for such a centre to initiate any executive action. I did that and hoped that the effort would lead somewhere.

I would like to know what you discussed in your brainstorming sessions and how did UGC come to know about your ideas. This can be especially helpful for students and young faculties who have ideas about creating such facilities either inside the universities or as a centre of excellence