Sharing the Thrills of Science

From Michael Faraday's captivating lectures that sparked the world's first one-way street to today, this article highlights the enduring importance of making science accessible to the public.

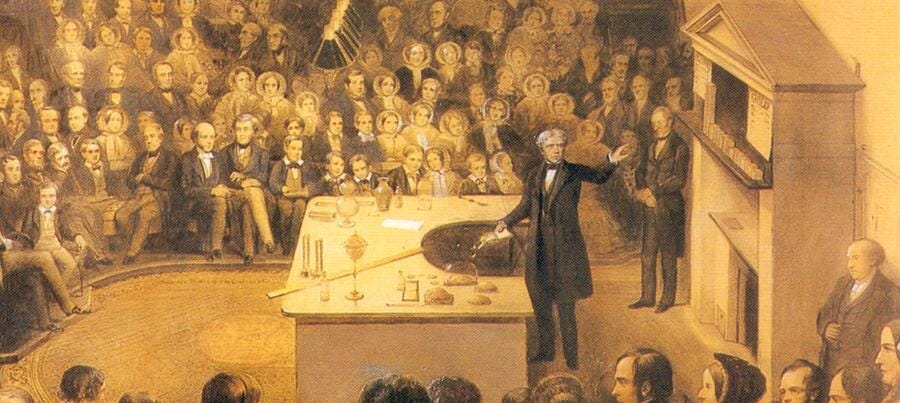

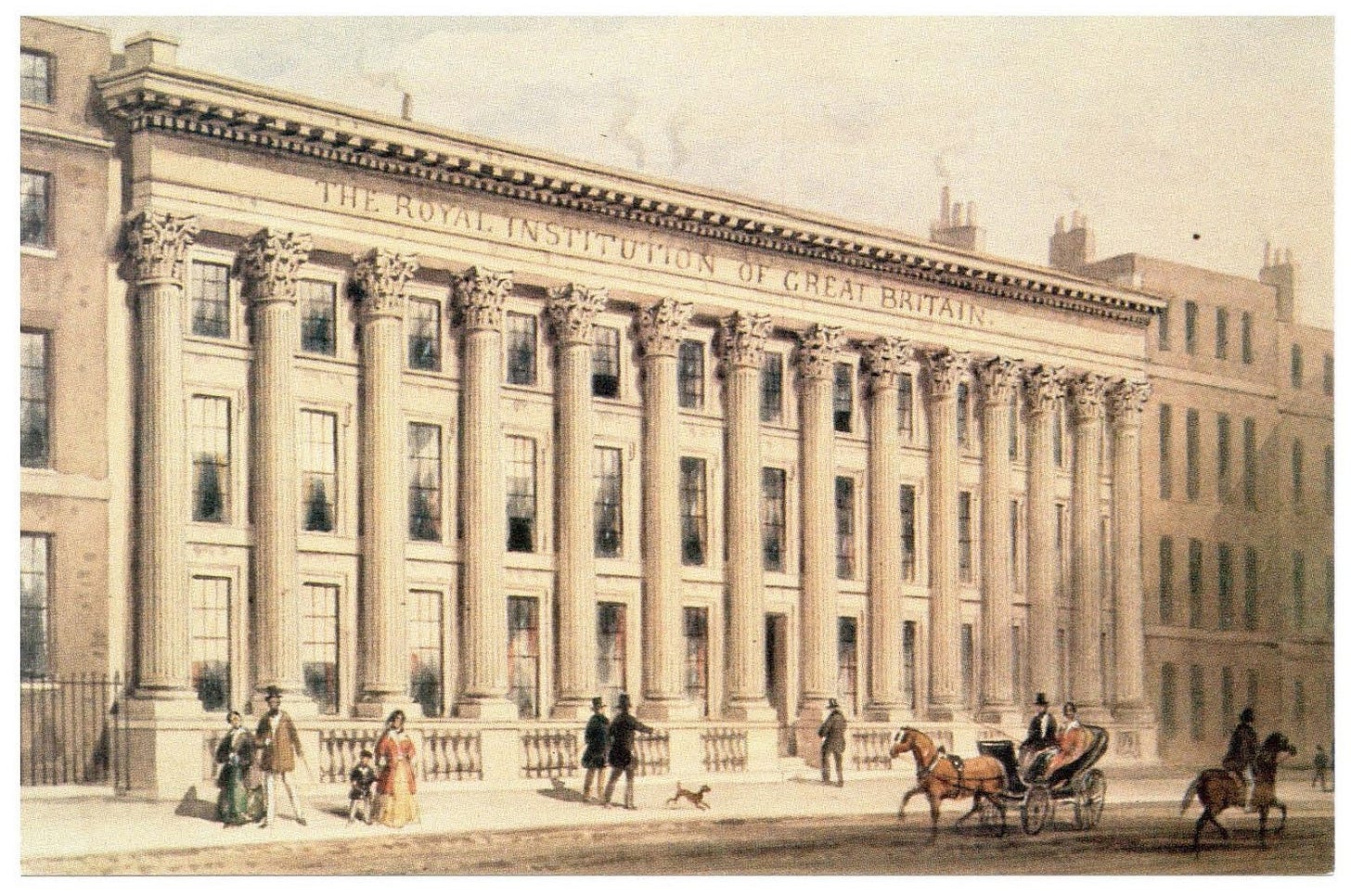

Which street was the first to be restricted to a “one-way” thoroughfare? You will get nowhere with your answer if you start searching amongst the world’s famous roads like Avenue Champs-Elysees, Oxford Street, or Broadway. The correct answer is “Albemarle Street” in London. The reason for this distinction is the location of a scientific institution on that street. Known as the “Royal Institution,” it was created in 1799 and made famous by the scientist Michael Faraday through his experiments and public lectures.

Faraday had a knack for presenting scientific discoveries in simple language, and his lectures inspired a liking for science in the general public. So much so that large crowds turned up for the programmes of the Royal Institution (RI), thus leading to traffic jams. The public authorities then took an unprecedented step. They declared Albemarle Street a one-way path.

An apocryphal story tells us that Faraday’s reputation reached royal ears, and Queen Victoria visited the Royal Institution to see for herself. Faraday showed her his laboratory, where he carried out his experiments on electricity and magnetism. He showed her how changing magnetic fields gave rise to electricity and how changing electric fields generated magnetic effects. Her Majesty was duly impressed by what looked like magic but asked the important question: “What is the use of all these devices?” Faraday is said to have replied: “Your Majesty! Do you ask what the use of a newborn baby is?” Indeed, in due course, those tiny desktop models eventually evolved to generate power to light up cities and trains to transport man and machine, in fact, giving a boost to the Industrial Revolution.

The question asked by Queen Victoria holds the key to a very important issue.

How does the general public get to know about what is happening in the scientific world?

The 19th Century saw science grow rapidly as a collection of experiments and observations that shed light on the workings of many natural phenomena. By the middle of the 20th Century, science was seen as an essential part of development. For healthy growth, funds are needed, which must be voted for in a democratic system.

It is instructive to see that of the many nations that acquired independence from colonial rule in Asia and Africa, only India appreciated the potential of science. Its first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, helped set up a scientific infrastructure in the form of research labs, manpower training and science-technology interaction. The effect of that infrastructure indeed speaks for itself today.

I recall the evening in Cambridge when, as an undergraduate, I attended an open lecture by Sir Lawrence Bragg. A Nobel Laureate, Bragg was then Director of RI and his aim was to highlight the importance of science popularization and the various programs followed by RI to bring science to the masses. While doing so Bragg also stressed the formality and punctuality observed by the speaker and the audience at all RI lectures.

For example, a Friday evening talk would begin at 9 p.m. and must end at 10 p.m. with no time allotted for introducing the speaker. A leaflet distributed in advance informs the audience of the synopsis of the talk and the speaker’s academic achievements.

I was once invited by RI to give such a talk. As per a tradition of over a century, the RI director would invite the speaker (and his lady) to a formal white tie dinner “at 7.30 for 8 p.m.” As per the precisely worked out timetable, the Director would conduct the lady to her front seat just a minute before 9 p.m. This is when the speaker enters the auditorium and begins the talk.

While showing us around the RI set-up, the Director forewarned us about the time protocol. He mentioned that some speakers had found it hard to implement, especially the need to end the talk precisely at 10 p.m. One speaker was so nervous that he ran away without giving his talk! Since then, the RI Director would lock the speaker in a small room and release him in time for entry to the auditorium.

To conclude this saga, I must acknowledge the guidance I received from Fred Hoyle. He not only showed me the necessity of keeping an open mind while doing scientific research but also the enjoyment one derives by conveying one’s findings to lay audiences. When I returned to India after some ten years of post-doctoral research, I continued my interest in science popularization. In a separate article, I hope to share my experiences, which have a typical Indian flavour.

Dr. Naralikar,

I enjoyed reading the blog. You shared many interesting facts while emphasizing science and punctuality. Please keep blogging.

Wishing you Health, Happiness and Science forever.

Sanjay

Dr. Naralikar, your stories played a big role in me developing interest in science. I think when it comes to popularisation of science, you are India’s Faraday !! Thank you.

One question comes to mind, other than IUCAA, are there institutes comparable to the Royal Institute doing similar work of science popularisation in India?