From Galileo to Chip Arp

Scientists, too, can be a bit stubborn: A tale of cosmic controversy and scientific dogma.

We began this series of blogs with a question about the objectivity of scientists. Ideally, one expects a scientific theory to always be on probation. Its predictions are tested from time to time. New, more sophisticated tests may come about, and by surviving them, the theory becomes more robust. On the other hand, the new test may show some inconsistency. It may happen that a re-examination of the new test shows that the inconsistency has gone away. In that case, the theory survives with fresh accolades.

Newtonian laws

An excellent example of how this process operates is seen in the way the Newtonian law of gravitation described planetary motion. Planets (apart from the Earth) Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn had been known for centuries. An addition to the list was made in 1781 when William Herschel discovered a new planet, which was named ‘Uranus.’ The observations of the planet over a few decades determined its trajectory around the Sun. It was expected that the trajectory would follow Newton’s laws of gravitation and motion. While there was broad agreement between theory and observations, there were small discrepancies that were worrying. There were three possible conclusions. (1) The Newtonian laws were wrong, (2) The observations were in error, or (3) There was a new feature in the whole picture that had been ignored.

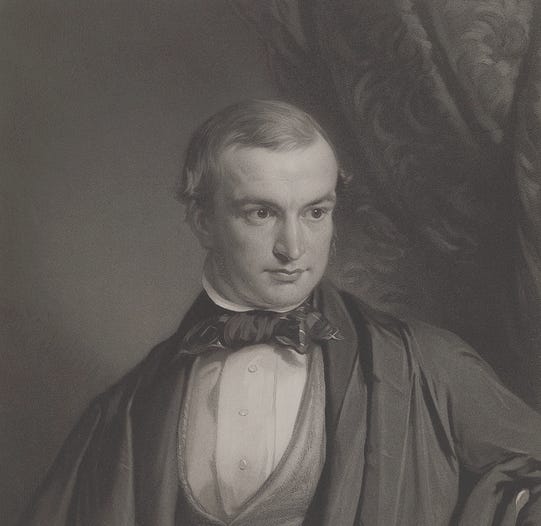

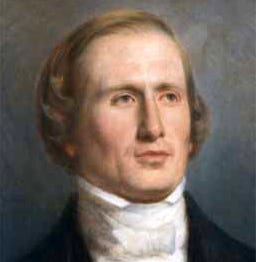

In the 1840s, two young astronomers, John Couch Adams from Cambridge and Urbain J.J. le Verrier from Paris, independently analyzed the data to conclude that the observations indicated the presence of a new planet near Uranus. The planet was looked for and found. It was named ‘Neptune’. The conclusion of this episode was thus another feather in the cap of the Newtonian system.

But that was not the end of the story! By the 1860s, a new problem surfaced. Mercury, the planet nearest to the Sun, showed a progress shift in the direction of the nearest point of its orbit, called the perihelion. The rate of shift was indeed very small…about 43 arc seconds in 100 years. [One arc second is the angle that is 3600th part of one degree.] By then, le Verrier was a senior astronomer in France, and he took it as a challenge. From his earlier success with Neptune, he sought to explain Mercury’s anomalous behavior as the result of a small intra-mercurial planet, which he named Vulcan. This time, he did not succeed…no such planet was found. The discrepancy remained, and it was resolved only in 1915. The general theory of relativity had the correct answer. But of the three alternatives mentioned earlier, it was the first that was operative!

Arp’s crusade

With these examples as background, we now describe a modern case relating to the anomalous findings of Halton C. (Chip) Arp. Arp began his career as an observational astronomer and as a former student of Edwin Hubble. Hubble’s work on galaxies, leading to the notion of the expanding universe, was considered the basis of modern cosmology. [See the first blog in this series.] Arp, in his own right, soon achieved a reputation for images of galaxies. His catalog of peculiar galaxies is recognized as an outstanding source of information about the extragalactic universe.

However, while carrying out these studies, Arp began to notice certain ‘anomalous’ cases. See the photographs for a couple of examples. In a typical case, you see two galaxies merging into each other or two galaxies connected by a filament of gas. If an astronomer looked at such a case, he would conclude that these galaxies are neighbours. But when the astronomer checks their redshifts, he would notice the anomaly. Hubble’s law would require the redshifts to be equal. But in some cases reported by Arp, they turned out to be different.

Arp began to get more such anomalous cases, and the explanation of such cases implied that Hubble’s law did not apply to them. To understand some cases, one could use the ‘escape route’ as follows. When one sees two galaxies together (as seen in the figures), they are not physically connected but happen to be projected one on top of the other. Such an explanation would be plausible if the background of farther galaxies were dense. In most cases, however, the background was sparsely populated, thus rendering the explanation rather implausible.

As Arp kept on finding such anomalous examples, the conventional cosmologists began to feel ‘uncomfortable.’ So much so that they began to find faults in Arp’s findings. There came a stage when leading astronomy journals began rejecting Arp’s technical papers. In the 1980s, Arp was denied access to important telescopes, including the Palomar telescope, where he had been a leading observer. The reason for the ban was that he was getting results that did not make sense! The implication was that the scientific establishment had made up its mind that Hubble’s law was absolutely sound and any result contrary to it was wrong.

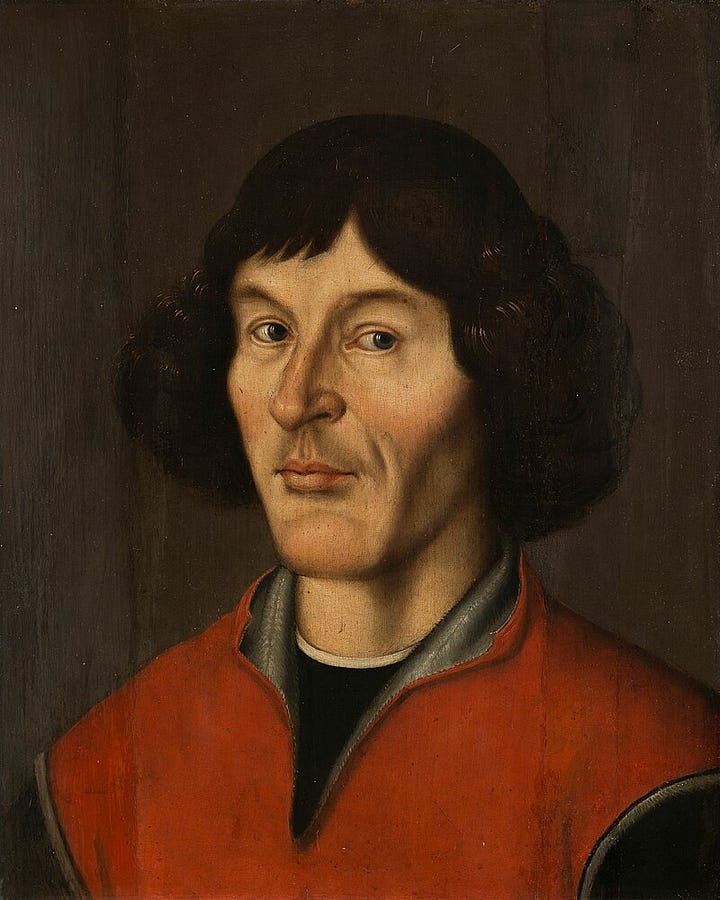

The treatment meted out to Arp showed that the establishment in modern times is qualitatively no different from that in Copernicus’s time six centuries ago. There are no inquisitions to impose conformism with the establishment, but in present times, the message is loud and clear: a funding agency will not support a nonconformist project. There are other examples where the proposer of a project ran into a dead end, as Arp did. Geoffrey Burbidge, a senior astronomer, recalled that his proposal to test the claim that redshifts of quasars are periodic was rejected. One referee of the project said that no doctoral work should be done on the project. A second referee said: nobody is going to work on this project because it is absurd!

This vicious circle is typical of the reason why anti-establishment ideas have not prospered.

I can do no better than quote a story going around in the corridors of the establishment. Once God applied for research funds to carry out studies of creation. The referees appointed to evaluate his proposal gave three reasons for rejecting it: (1) It had been a long time since he last worked on the topic. (2) No one else had been able to repeat his experiment. (3) All his work to date was not published in a refereed research journal but was published in a book.

History tells us how, in the times of Copernicus and Galileo, the confirmed belief was that the Earth is fixed and the Sun and the planets go around it. The Church subscribed to it, and it was heresy to say that the Earth moves around a fixed Sun. The book written by Copernicus was banned, and anybody supporting it was subject to trial by the Inquisition. Galileo was a strong supporter and was made to recant. While he officially did so, he kept his belief in Copernican theory. It is said that when he recanted, he muttered, " Eppour si mouve ...But it moves".

I could not agree more, Prof. Narlikar. While patently wrong ideas or lines of research should be discarded, unfashionable ideas should not. JC Bose's work on the response of plants to stimuli, Alfred Wegener's idea of Pangea which was scoffed at by established geophysicists of his time, the initial scepticism towards a Bahcall for a particle physics resolution of the solar neutrino problem are similar examples.

Marvelous.