Disputations and Controversies, Part 2: The Mystery of White Dwarf Stars

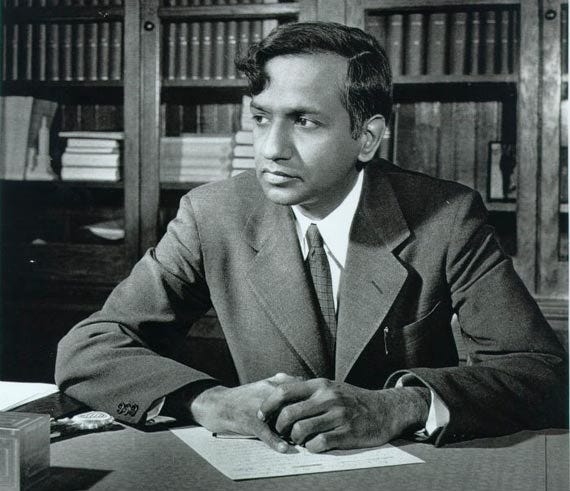

An Indian student's groundbreaking theory on the fate of stars is ridiculed by a renowned scientist, only to be vindicated and awarded the Nobel Prize half a century later.

The Chandrasekhar Limit

In 1930, an Indian student sailing to England on his way to Cambridge for higher studies started thinking about the following problem: “Do the electrons in a degenerate state move according to Newton’s laws, or do they move according to the special theory of relativity?” That student's name was Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar.

When one travelled by boat to England in those days, one got a lot of free time. Normally, travellers spent it eating, drinking, reading novels or playing games like cards, table tennis or chess. But Chandrasekhar was absorbed in working out the mathematical details of the above question. As in the analogy of the cup being filled with water, he realised that if the electron energy level rises to a very high level because of their being stuffed in a limited space, the electrons will tend to move very much faster, with some of them approaching the speed of light.

Fowler had taken it for granted that the speed of electrons would follow Newton’s laws of motion. But with the speed of electrons approaching the speed of light, Chandrasekhar felt that special relativity should be used.

Later, after going to Cambridge, Chandrasekhar kept working on this problem. By 1935, he had some important results. They could be stated in brief as follows:

The higher the mass of the star, the higher the temperature at its centre.

The higher the temperature at the centre, the larger the velocity of electrons there. Hence, in a star of higher mass, the electrons will tend to move at speeds close to the speed of light.

Therefore, in the case of more massive stars, the pressure inside should not be computed as per Newtonian laws of motion, as was done by Fowler, but as per the laws of special relativity.

When we apply the new laws, we find that only stars of mass below a critical limit can get the advantage of degenerate pressure. Stars with mass above this limit cannot call upon degenerate pressure for their equilibrium. This critical limit of mass is 1.44 Mʘ, where Mʘ is the mass of the Sun. All the observed white dwarfs must, therefore, have masses below this critical limit computed by Chandrasekhar. Because stars more massive than this limit cannot attain equilibrium, such stars will contract under their gravitational force.

Chandrasekhar sent his results to the Royal Astronomical Society for publication. (Chandrasekhar now was not a student, but a Fellow of Trinity College.) He was invited to present his results in a monthly meeting of the Society, held on the second Friday of every month. In such a meeting, which lasts about an hour and a half to two hours, a few invited astronomers present their new results to others. Experienced astronomers, as well as those entering the field, are present on such occasions. Often, there are controversies to enliven them, such as the famous debates between Milne and Eddington, Hoyle and Ryle. The meeting of January 11, 1935 was also destined to be a memorable one.

Kameshwar Wali, the biographer of Chandrasekhar has described the event as recalled by Chandrasekhar. The story is briefly as follows:

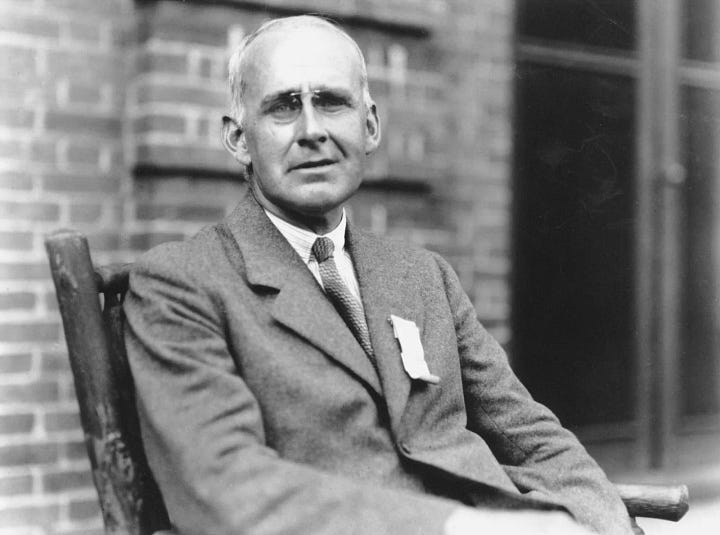

The father of the science of stellar structure, Eddington, was himself a Fellow of Trinity College. What was his reaction to Chandrasekhar’s work?

On the night of January 10, 1935, Eddington and Chandrasekhar met at dinner at the High Table in Trinity College. Eddington knew about Chandrasekhar’s work and that he was presenting it at the meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) the following day.

“I have asked the Secretary of the Society to give you extra time to speak.” Eddington himself told Chandrasekhar. Chandrasekhar thanked him, thinking that Eddington supported his point of view.

But the situation was the exact opposite! Eddington was in total disagreement with Chandrasekhar’s conclusions! He did not disclose to Chandrasekhar that he, too, would be speaking on the topic of degenerate pressure on the following day and that he was going to strongly criticise Chandrasekhar’s conclusions. So the speech by Eddington at the RAS came as an unexpected blow to Chandrasekhar.

As planned, Chandrasekhar presented his work in the meeting of January 11, and the President of the Society asked Eddington to express his views on it. The views of an established astronomer like Eddington were naturally going to be of great importance. Chandrasekhar was confident that his conclusions were correct and that experienced astronomers like Eddington would fully support and endorse them.

But what happened was otherwise.

In his speech Eddington ridiculed the new results. He forcefully argued that the hypothesis as well as the conclusions of Chandrasekhar were physically meaningless. When an established scientist in the field passes such a strong judgement on his work, surely a young scientist must feel very crestfallen and dejected.

Eddington went on to say that the conclusions drawn by combining quantum theory and relativity were wrong, because such a combination is untenable. Moreover, he argued that, if the limit on the mass of white dwarfs were correct, what about the stars more massive than the limit? These stars would keep on contracting and in the end their force of gravitation would grow so strong that it would stop even the light rays! “I think there should be a law of nature to prevent the star from behaving in this absurd way”, he said.

When an international authority on relativity like Eddington gave such an opinion, the other scientists present also thought that Chandrasekhar’s work was of dubious validity. In fact, people like Niels Bohr, Pauli, Rosenfeld etc., who were quantum physicists, knew that Eddington’s reasoning was wrong, but they did not openly support Chandrasekhar. It may be for two reasons. First, they did not want to enter into controversy with an established scientist like Eddington, and second: because at that time astronomy was not considered to be a top ranking science, and so other scientists did not take much interest in it.

It is observed time and again in science that an intrinsically correct theory cannot be suppressed forever by a hostile majority opinion or established leaders in the field. The evidence does accumulate, sometimes slowly, to support the correct theory. The theory which was ridiculed on January 11, 1935 earned the Nobel prize after 48 years. Though late, the father of that theory got justice in the 73rd year of his life.

The irony of the debate between Eddington and Chandrasekhar is worth noting, however. When he criticised the Chandrasekhar limit, Eddington had worried about the fate of more massive stars. His description of the ever contracting stars, which he considered too ridiculous to be real, in fact applies to black holes. Today nobody doubts the existence of black holes. Nature allows things more fantastic than human imagination. If Eddington had supported Chandrasekhar and worked out the fate of the more massive stars, he would have earned the credit of theoretically predicting black holes!

Very nicely written article. It not only tells about the technical details of Chandrashekar limit, but also how near Eddington was to predict blackholes. Why only Eddington, even Chandrashekar sir could have predicted blackholes, following Eddington's arguments. Really like the story telling and the takeaways.

Prof Narlikar, Dear Sir, thanks to one of our alumni members drawing our attention to your blog posts, we had have an opportunity to interact with the main architects of the steady state theory. It is a great pleasure to read your articles after a long lapse of time in the 1980s and they refresh our memories on the foremost debates taking place within the physics community over the theory of Black holes. The post also reveals to us that information that is not revealed from reading books by Prof Stephen Hawking or Nobel laureate Sir Roger Penrose. Further, it demolishes the idea held by Nobel laureate Max Planck on how science progresses or hypothesis are accepted. as you have rightly said, evidence gathers slowly to reveal the Truth. Looking forward to many more refreshing and memorable posts from you good sel. Have a nice day. Best Regards Sanjeev