The IUCAA Story: A first-person account of how a unique astronomy institution was created.

Part1: The Background.

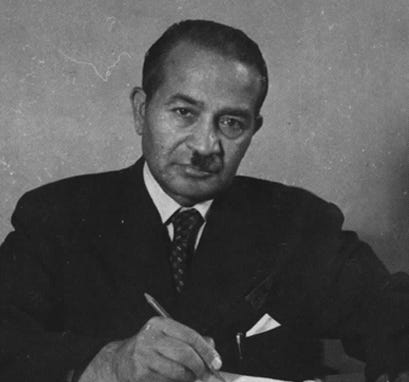

On December 28, 1992, Chairman Ram Reddy of the University Grants Commission dedicated a new institution called the ‘Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics’ to the Nation. The occasion was marked by a lecture by Nobel Laureate Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar and the start of a Foucault Pendulum.

The newly launched institution was a unique one of its kind and would soon be creating waves in the world astronomical community. Not surprisingly, because of its long name, it soon became known by its acronym ‘IUCAA.’ Its reputation grew rapidly, and soon it became known internationally. As a scientist associated with IUCAA from the beginning, I am often asked how it came about. So here is a detailed account of IUCAA’s genesis and early life.

In the 1940s, it was becoming clear that the British rule of India would end soon, and the new nation would face several challenges. On August 15, 1947, when the British left the country to fend for itself, it was important that an enlightened leadership took over the task of guiding the new nation. Fortunately, the first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, was aware that science and technology would play a key role in the nation's development. So, he took leading scientists and technocrats in confidence while making key decisions that made it possible for the new nation to catch up with the developed nations. Department of Atomic Energy (DAE), Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), and University Grants Commission (UGC) are some of the important outcomes of those early days. Homi Bhabha, Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar, C.V. Raman, M.S. Swaminathan, D.S. Kothari, and Vikram Sarabhai were some of the leading lights. The outcome of Nehru’s vision was the growth of research institutions and centres of excellence under Government Departments like DAE, CSIR, etc., which led to a boost in scientific research.

A glance at the history of post-World War II shows that while several countries gained independence from colonial domination, only India created and sustained a dynamic feeling for science and technology (S&T). The S&T infrastructure created in India in the 1940s has helped strengthen advances in various fields, such as space technology, agriculture, medicine, etc.

While creating this infrastructure, it was hoped that the university system in India would also grow and participate in the S&T progress. The universities in advanced countries serve as the main caterers of higher education. Universities like Oxford and Cambridge, Harvard and Princeton have successfully combined the teaching of students with advanced research. Good students are attracted to a research career if they see good teachers at a university campus. Also, interacting with students helps teachers bring freshness to their research. Many successful universities abroad have managed to create and maintain academic excellence. These universities are centres of excellence not only in technical subjects but also in humanities, arts, classics etc. In fact, Jawaharlal Nehru had hoped that this would happen when S&T launched in India. The headquarters of UGC in New Delhi have on display the following statement by Nehru:

“A university stands for humanism, for tolerance, for reason, for the adventure of ideas and for the search of truth. It stands for the onward march of the human race towards ever higher objectives. If the universities discharge their duties adequately, then it is well within the nation and the people".

While Nehru was aware of the role of universities in the building of a nation, several reasons, such as shortage of manpower and funds, political interference, compromising with quality, etc., made it difficult to achieve spectacular growth in the university sector. Ironically, the emergence of autonomous centres of excellence in various subjects diverted attention away from universities, creating problems for both. The autonomous centres, being isolated from university students, complained of a shortage of good students coming to them while the typical university student missed the excitement of research in his university department. What was needed and was missing was a close connection between a university and an autonomous centre of excellence.

However, if we try to create such a centre exclusively for a university, we encounter two main problems. Firstly, if such a centre is provided for one particular university, other universities would demand such centres too. It will be prohibitively expensive to satisfy them all! Secondly, a typical university will not have enough users for the facility, which will result in it remaining idle most of the time. Is there a way out of this conundrum?

We now look at an example in the USA that has worked. In astronomy, a sophisticated telescope plays a key role in bringing fresh data on the universe. In the 1970s, a state-of-the-art 4-metre telescope was expected to be launched in an observatory in Tucson, Arizona. While several universities were interested in such a telescope, its basic cost and regular maintenance were too high for a typical university. There was also the issue that if the telescope could function on, say, 200 nights in the year, the users from a single university would not have sufficient observing programs to keep it busy. To address these issues, a concerned group of universities (some twenty of them) formed an “Association for Research in Astronomy” (AURA) to acquire and control the telescope. The costs were shared by members of AURA. Thus, if a university were expected to keep the telescope busy for 20 nights a year, it would contribute 10% of the total budgetary cost. Therefore, the telescope is affordable for each participant university, and they keep it busy on all of its useable nights.

Operation of an advanced but expensive facility on a shared basis has become common in scientific research, not just in astronomy but also in other subjects. For example, the particle accelerator at CERN is used by several nations on a cost-shared basis. The university sector in India has adopted this modus operandi successfully, as we will describe in our next blog.

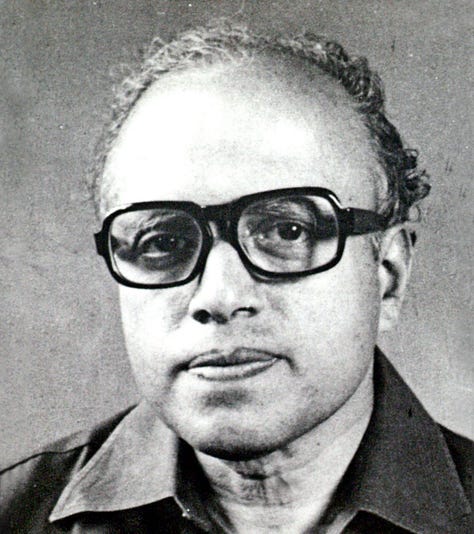

Thank you for bringing back some great memories. We were in school - maybe 8th or 9th and IUCAA through some program offered 2 students from my school some summer program there. I applied but my school sent some other students. In my frustration, I looked up your mailing address and sent you a letter expressing my interest in the program and desire to get to see IUCAA. I didn’t expect much to happen.

Lo and behold, a few days later, I get a reply from Dr. Jayant Narlikar himself!! What excitement! I was thrilled to have received official mail from him. To me, it was as if Amitabh Bacchan had replied to a fan… and I was a fan (still am). While you couldn’t let me into the program, you were generous and offered a visit to IUCAA. I did visit, but it was later (I don’t remember what the occasion was). It was an amazing experience. A couple of years after THAT I had the opportunity to visit again, where one of the students there gave us some lessons on the basics of quantum physics and helped us learn the basics of quantum computing theory. I remember many hours spent in the library there (such a beautiful and well equipped place)… but what struck me the most was the desire to genuinely give students a taste of science. What was possible. Make us excited about science!

Thanks for all of that. But to you and the wonderful people at IUCAA.

Oh and I forgot, the lectures at IUCAA when school students were allowed to attend!! Again, stuff that got us all super excited about science. Thanks again for such great programs